Persistent Eisenhower Cardiologist Solves a Mystery

Sometimes, however, astute diagnosticians need to look for a zebra.

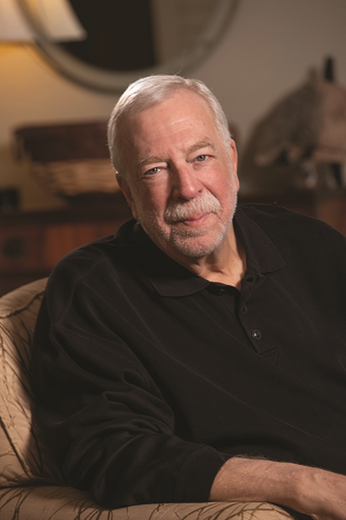

This was the case when Palm Desert resident and retired broadcasting executive Barry Gorfine, 67, came to see Board Certified Eisenhower Cardiologist Eric Sontz, MD, last April.

The year before, Gorfine was treated at another hospital for pericardial effusion (fluid around the heart). But after undergoing a procedure to relieve the fluid buildup, Gorfine continued to get worse, experiencing extreme fatigue, loss of appetite, and generally feeling lousy. He was given a diagnosis of pericarditis, inflammation of the sac-like tissue (pericardium) that surrounds the heart. Gorfine was also having symptoms of atrial fibrillation, a heart rhythm disorder.

Frustrated that his condition wasn’t improving, Gorfine had switched his Medicare plan from an HMO to a PPO with a bigger provider network, giving him the flexibility to see another cardiologist. Based on recommendations from two friends, he went to see Dr. Sontz.

“He presented to me with symptoms of heart failure, including extreme shortness of breath with exertion,” Dr. Sontz recalls. “But as we started doing more diagnostic tests, we discovered clues that had been missed.”

Dr. Sontz performed a simultaneous right and left cardiac catheterization to evaluate for constrictive pericardial disease versus a restrictive cardiomyopathy. He then ordered a technetium pyrophosphate scan once he diagnosed the restrictive cardiomyopathy. Dr. Sontz suspected that Gorfine’s heart was stiff due to cardiac amyloidosis — stiff heart syndrome — a disorder caused by deposits of an abnormal protein (amyloid) in the heart tissue that take the place of normal heart muscle. In Mr. Gorfine’s case, this abnormal amyloid is produced in the liver.

Cardiac amyloidosis is a rare disease, affecting only about 4,000 Americans a year. It is typically diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 65 and is more common in men than women.

“That Mr. Gorfine also had intermittent atrial fibrillation was another clue pointing in this direction,” Dr. Sontz says, noting that cardiac amyloidosis can also affect the way electrical signals move through the heart (the conduction system), causing heart rhythm disorders (arrhythmias) and faulty heart signals (heart block).

But Dr. Sontz had seen only three cases of cardiac amyloidosis in his 20-plus-year career — underscoring just how rare this condition is. What prompted him to think “zebra” when it came to Gorfine’s symptoms?

“When a patient isn’t getting better, I am excited by the diagnostic challenge,” he says. “The standard approach wasn’t giving us any results. Mr. Gorfine continued to have significant symptoms despite an extensive workup. Any other physician would have done the same.”

Dr. Sontz referred Gorfine to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Its Heart Institute is home to one of the world’s top experts in cardiac amyloidosis, Jignesh K. Patel, MD, PhD. He performed some additional advanced testing and confirmed Dr. Sontz’s initial diagnosis.

“Dr. Patel was very impressed with Dr. Sontz,” Gorfine says. “This disease is so rare; he thought Dr. Sontz was great to have recognized it.”

Although there is no cure for cardiac amyloidosis, there are therapies available today that can potentially stabilize it, helping patients stay alive until they can undergo a heart transplant.

“That’s the only way to fix this problem,” says Gorfine, and he has begun the rigorous screening process to get his name on the transplant list. In the meantime, he is taking a newly FDA-approved drug that normally costs $225,000 a year — but the manufacturer’s patient assistance program arranged for him to get it for free. He also has been offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial of another new drug in development, which he is considering.

“The chances of me getting a heart transplant are not great because I’m 6 feet 5 ½ inches tall, and they have to match the donor heart to the size of the patient,” he says. “So I hope the drugs work.

“I’m not afraid of dying,” he says, candidly. “But I am afraid of missing things. I have two kids and a wonderful wife, so I want to be around for all those family markers. And I’d like to see the Dodgers win another World Series — but who knows if I’ll live that long?” he says with humor.

“I’m incredibly appreciative that I was diagnosed when I was so that I have access to these new drugs,” he adds. “They’re not a guarantee, but it does give me hope.”

To contact Eisenhower Desert Cardiology Center, call 760.346.0642.